The term frozen shoulder is a condition associated with pain and stiffness in the absence of a demonstrable cause. The term “frozen shoulder” is often overused and applied to any person with a stiff and painful shoulder. A stiff shoulder can be divided into a primary frozen shoulder and secondary stiff shoulder. The primary frozen shoulder or true frozen shoulder is as defined above with a painful and stiff shoulder joint in the “absence of a known intrinsic shoulder disorder”. A secondary stiff shoulder is shoulder pain and stiffness from any other causes such as an injury, for example, a fracture, tendon or cartilage tear. It can also occur due to conditions unrelated to the shoulder.

The precise cause of this condition remains poorly understood despite much research. The condition of frozen shoulder is very common. 2% – 5% of the general population develop a frozen shoulder. The other significant risk factors are diabetes and thyroid disease.

What causes a frozen shoulder?

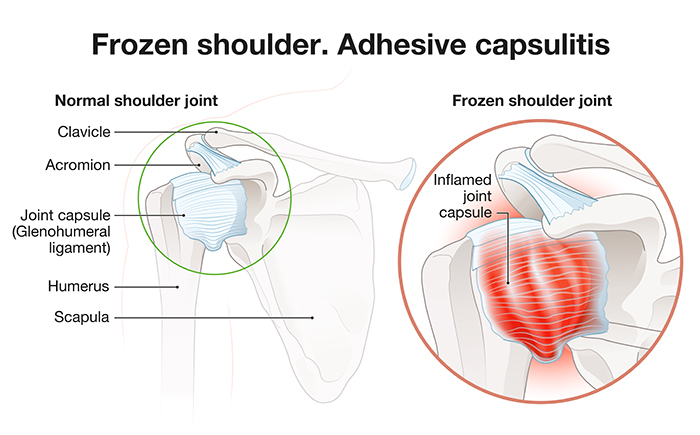

The shoulder joint is a ball and socket joint similar to the hip joint but with strikingly more mobility. In fact it is the most mobile joint in the body. The surrounding cartilage and “soft tissue capsule” which includes the ligaments provide the shoulder with stability but still allow the enormous range of motion. In a frozen shoulder the soft tissue capsule initially becomes very inflamed causing a deep ache in the shoulder joint radiating down the arm. After the development of inflammation, the surrounding soft tissue capsule contracts like a scar, which restricts shoulder motion causing increasingly severe stiffness.

Diagnosis

By definition, in the primary frozen shoulder, there is no known underlying disorder. As x-rays, ultrasounds, and even MRIs are good at picking up damaged tissues, they cannot usually see inflammation. These investigations must therefore be essentially normal. So, we, therefore, rely on typical clinical features to suggest the diagnosis of a frozen shoulder.

The only investigation which can really assist in confirming the diagnosis of a frozen shoulder is an MRI arthrogram, in which dye is injected into the shoulder joint and then an MRI is performed. In a normal shoulder joint the surrounding capsule is extremely thin and elastic and one can see distension of the capsule with a fluid called the axillary recess (above figure). In the presence of a frozen shoulder, the MRI looks normal except there is no distension, confirming a tight capsule which is diagnostic of a frozen shoulder.

Treatment

Treatment options include simple medications may be all that is required. These include pain medications and anti-inflammatories.

Clinical interventions which I will discuss include Physiotherapy, Cortisone injections, and occasionally, arthroscopic capsular release.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy can be helpful in the first few months following the onset of symptoms, when the inflammation has settled, physiotherapy and stretching exercises might accelerate recovery in the range of motion

Cortisone injections

These are used to reduce inflammation. The correct site for the injection is critical. combined injections are performed into the bursa. Primary frozen shoulders and Ultrasound-guided injections into the shoulder joint have been shown to be far more successful in reducing the pain.

Manipulation under Anaesthesia

Manipulation under Anaesthesia (MUA) is where the patient is given a general anesthetic, and then their shoulder is forced until the capsule tears. The procedure is helpful for patients with Frozen Shoulder, particularly for patients who haven’t developed a severely thickened and fibrous capsule.

Arthroscopic capsular release

If the symptoms do not respond well to the above modalities and pain and stiffness are prolonged or intolerable, an arthroscopic capsular release can be performed. It is a key-hole day-surgery procedure where the inflamed and thickened capsule is released. It requires typically 3 tiny incisions. After the procedure, you are encouraged to use your shoulder as soon as comfort allows. You do not need to wear a sling and can return to driving and light activities within a few days. Full recovery typically takes from 6 weeks to 3 months. This provides much quicker relief of the severe pain and accelerates recovery of the range of motion by many months or years.